In the vast expanse of northern Sweden, where temperatures sometimes plummet to -30°C in winter, simply travelling to work can involve a round trip of hundreds of kilometres. To address this, more and more people are finding new ways to create jobs locally.

The country’s most northerly county is Norrbotten, which is bigger than Austria or Portugal yet has a population of just 250,000. Nestled in the south of Norrbotten is the tiny community of Glommersträsk – home to just 300 people and the location of a thriving business owned by 76-year-old entrepreneur Bo Lundmark.

As a former telecommunications engineer, Bo was determined to start a business that would create secure, local employment for fellow residents in Glommersträsk when he formed Glommers Miljöenergi AB in 1996. As well as creating local jobs, he was keen to ensure that the business was founded on sustainable principles and used local, renewable natural resources.

Today, Glommers Miljöenergi AB is a thriving business that employs six villagers, produces biofuels for the community, processes and sells a range of products from local wild berries, rents apartments, and harvests grass to be used as animal bedding.

“Entrepreneurship has been in my family’s blood for generations,”

said Bo. “I had farmed animals as a hobby since moving to Glommersträsk in 1975 but in 1990 I sold the animals but continued to cultivate reed canary grass and 1996 Glommers Miljöenergi was started ,” said Bo.

“My main aim was to create profitable local jobs based on the extraction and processing of local raw materials, but circular thinking has been an important focus from the beginning. That’s what attracted me to producing grass.

“We grow reed canary grass from seed, which can be used for animal feed or bedding, depending on when it is harvested. All vegetation captures carbon and when reed canary grass is used as bedding for livestock, it also stores the carbon in the soil when the resulting manure is used as a fertiliser.

“We seem to have forgotten that the cheapest way of capturing carbon is through photosynthesis.”

Bo’s business has had a significant impact on the lives of his staff, particularly Sales and Site Manager, Lennart Wigenstam. As a father of ten children, family time is a big priority for Lennart and working at Glommers Miljöenergi AB for the last 13 years has enabled him to spend more time at home. Before this, he had his own business refurbishing floors which involved travelling thousands of kilometres across northern Sweden every year.

“I feel very lucky to be able to work so close to home as there are very few job opportunities in this part of Northern Sweden – it’s such a vast area,” says Lennart. “One of my sons has to travel 400km every week to get to work and another son has to fly to Stockholm for his job. This has a big impact on their lives so you can see why it’s important that more jobs are created within small rural communities like Glommersträsk. I’m also very glad to work for a local business that benefits the environment as well as the community.”

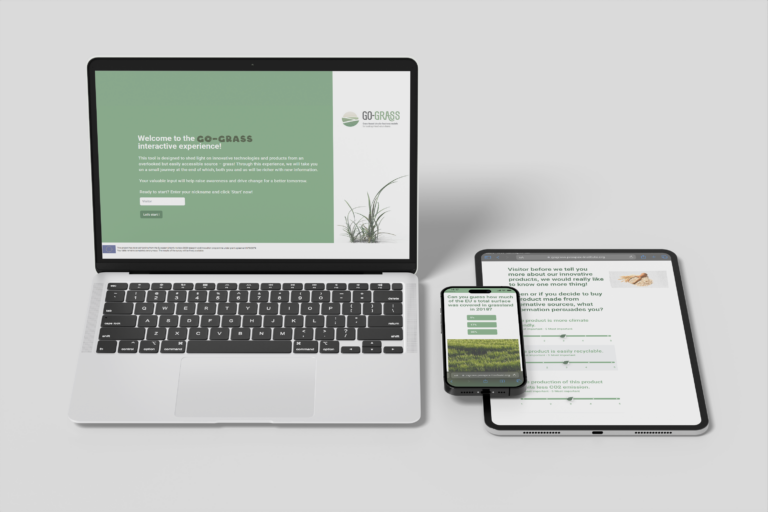

Having built a flourishing and sustainable bio-based business that benefits his local community, Bo is now aiming to help other small rural communities across Europe by creating a model for his business that can be replicated. He is doing this as part of EU-funded project GO-GRASS which is developing a set of small-scale bio-based solutions to unlock the overlooked potential of grassland across Europe and create new business opportunities for rural areas.

“I think it’s important to be able to share an experience in an area important for both the climate and a living countryside,” says Bo. “We believe our business model can be replicated all over Europe, for the benefit of many small rural communities.

“Reed canary grass can be used as both animal feed and bedding, depending on when it is harvested. As bedding, it is harvested in the spring as soon as the land is dry enough to carry the machines. The grass is dried naturally when laying out in the field during winter. As feed, it is harvested in summer or autumn.

“We heat treat the grass and compress it into briquettes, to achieve better density, reduce dust and improve hygiene as the heat minimises and kills bacteria and helps prevent seed emergence when the manure and bedding is later used for cultivation.”

He sells the bedding material to customers within a 200-300km radius, for use with horses, poultry and pigs. His main competition is sawdust and wood shavings, which are still the most popular types of bedding.

“I’m trying to get more people to realise that grass is the most climate-smart bedding in a circular society, but some people are old-fashioned, and they don’t want to change.”

“I do hope to expand our operation, which will mean using more land to cultivate reed canary grass but that’s not a problem here in Northern Sweden where so much of the land is unused so there are no competing interests.”

Bo’s participation in GO-GRASS is not the first time he has partnered in an international project:

He has worked with the Research Institute of Sweden (RISE) for many years and was previously involved in an Swedish Government Agency for Development Cooperation (SIDA)-funded project in Tanzania, in which he helped communities identify a local grass that could be compressed into briquettes and used as fuel instead of wood taken from local trees.

“I think it’s very important that we harness the potential of grass all over the world, for the benefit of people, communities and the environment,” says Bo.

In addition to Bo’s business model for producing animal bedding from grass in Sweden, GO-GRASS partners in three other countries are testing other grass uses. In Germany, researchers are producing a model based on using grass to produce biochar; in Denmark protein is being extracted from grass to enrich the diets of farm animal; and in the Netherlands, researchers are using grass to produce paper and packaging.

As the project develops, online business modelling tools will become available on the GO-GRASS website to help communities across Europe replicate these models and unlock the potential of grasslands for the benefit of all communities.

– Interview by Charlotte Reid for GO-GRASS –